Abstract

Pleomorphic adenoma is a benign neoplasm of the salivary glands. It is the most common type of salivary gland tumour and the tumour most commonly found in the parotid gland. Clinical diagnosis of a parotid gland neoplasm can be difficult, particularly when the lesion is located deep within the gland. Although usually asymptomatic, pleomorphic adenoma may exhibit symptoms mimicking those of conditions such as temporomandibular joint disorder. This case report highlights the difficulties of diagnosing this type of tumour and the importance of communication between physicians and dentists to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common benign salivary gland neoplasm, frequently arising within the parotid gland.1 Pleomorphic adenoma (mixed tumour) is composed of both epithelial and myoepithelial cells within a mesenchymal-like stroma.2 This tumour usually affects middle-aged adults and occurs in women slightly more often than in men.3 The lesion occurs most often in the parotid gland but may also arise in the submandibular, sublingual and minor salivary glands.4 Pleomorphic adenoma typically presents as a slow-growing, painless, firm mass and is only occasionally associated with facial palsy or pain.1

The superficial lower pole of the parotid gland is the most frequent site of occurrence, but 10% of all parotid tumours are located in the deep lobe of the gland.5 Tumours of the parotid gland may physically impede mandibular movement and may cause muscular paralysis or alter the sensations controlled by cranial nerves 5 and 7.6

The diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma is ultimately made by histopathologic examination, whereas tumour size, location and extent are determined by advanced imaging. Surgical removal is the best course of treatment, given the tendency of these tumours to recur.1 Although they are benign by nature, a small percentage of cases are associated with malignant transformation.2

The case report presented here describes pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland in a patient who exhibited symptoms suggestive of temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD).

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman with a history of gastroesophageal reflux and previous thyroidectomy was referred to the department of dentistry at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital with an approximate 24-month history of left-sided facial discomfort. Medications included levothyroxine and omeprazole. The patient had previously sought treatment from several dentists, 2 otolaryngologists and a neurologist, all of whom had been unable to diagnose the problem. At the outset of the consultation and history-taking, the patient described her pain as a dull “discomfort” in the area of the left temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and zygoma.

Clinical evaluation demonstrated sensitivity to palpation in the area of the left TMJ, in addition to intraoral tenderness to palpation in association with the left coronoid insertion of the temporalis muscle and the lateral pterygoid region. A subtle firmness was appreciated just below the TMJ, primarily on the basis of difference from the other side. The patient reported no reduction in salivary flow or changes in the degree of pain with mastication. Clinical and panoramic radiological examinations showed no evidence of contributory dentoalveolar disease that might explain the symptoms.

In light of the history and the clinical and radiographic findings, the provisional diagnosis was a neoplasm with associated TMD-like symptoms. There was no urgency to undertake further dental imaging, as the initial suspicion was a neoplasm, which would require magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A trial injection of local anesthetic in the area of the left coronoid insertion of the temporalis muscle decreased the patient’s discomfort, and follow-up trigger-point injection of steroid was administered. However, the relief was short-lived.

At the time of this consultation appointment, the patient was referred for an otolaryngological evaluation, with a request for MRI. The otolaryngologist did not appreciate any palpation abnormalities and concluded that the problem was a dental or TMD concern. Nonetheless, the otolaryngologist ordered MRI (as per the referral request), because of the patient’s history of persistent discomfort in the TMJ region.

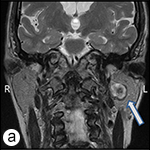

MRI revealed a lesion of 1.9 cm diameter within the inferior aspect of the deep lobe of the left parotid gland. T2-weighted imaging showed a peripheral area of hyperintensity, with an ill-defined central area of low signal intensity. Intravenous injection of contrast medium caused strong enhancement of the mass. There was no lymphadenopathy or contrast enhancement of the facial nerve (Fig. 1). The differential diagnosis included various benign lesions, such as pleomorphic adenoma, but it was essential to rule out malignancy, such as adenoid cystic, mucoepidermoid or acinic cell lesion. The patient was referred to a surgeon (Dr. Ian Witterick of Mount Sinai Hospital) for further management.

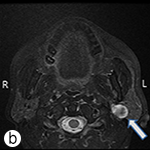

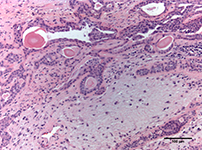

The lesion was excised, and pathological examination revealed benign pleomorphic adenoma (Fig. 2). Five lymph nodes were also removed for examination, and no malignancy was identified. Left facial nerve function was weak postoperatively but improved steadily over time. The patient was disease-free at 6 months (Fig. 3) and 24 months after surgery, as confirmed by MRI. She was scheduled for subsequent follow-up appointment and MRI 1 year later (i.e., 36 months after surgery).

Figure 1: Coronal T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced (post-gadolinium) (a) and axial T2-weighted (b) magnetic resonance images. In each image, the arrow points to the lesion, which is located within the inferior aspect of the deep lobe of the left parotid gland. The lesion has peripheral hyperintense signal with an ill-defined central area of low signal intensity. The radiographic features were suggestive of a benign lesion, such as pleomorphic adenoma; however, a low-grade salivary malignancy could not be ruled out.

Figure 2: Photomicrograph of the tumour illustrates chondromyxoid stroma, with epithelial and myoepithelial cells forming the ductal structures (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 magnification).

Figure 2: Photomicrograph of the tumour illustrates chondromyxoid stroma, with epithelial and myoepithelial cells forming the ductal structures (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100 magnification).

Figure 3: Coronal T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced (post-gadolinium) (a) and axial T2-weighted (b) postsurgical magnetic resonance images. There is no evidence of recurrent or residual disease.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of TMD includes dental pain, neuralgias, central lesions, somatoform disorders and disorders of the temporomandibular apparatus (including neoplasms).6 Tumours, both benign and malignant, can arise within the joint, the associated tissues or the parotid gland, any of which may cause symptoms similar to those of TMD.6-8 A parotid gland tumour located in the deep lobe is a possible cause of such symptoms.9

TMD is a collective term encompassing numerous clinical complications involving the muscle of mastication, the TMJ and associated structures.10 TMDs represent a major source of nondental pain in the orofacial region.10 When patients present with orofacial pain or dysfunction, TMD is often (mis)diagnosed, without adequate consideration of other potential causes.6

Neoplasms presenting as TMD are rare6 but well documented in the literature.11 Neoplasms that have been reported to mimic the symptoms of TMD include squamous cell carcinomas,12 salivary gland tumours,13 sarcomas9 and malignant peripheral neural sheath tumours.7 These tumours arise from numerous structures in and around the TMJ, including the parotid gland.11 To the best of our knowledge, pleomorphic adenoma arising in the parotid gland and mimicking TMD appears to be unusual, since the majority of tumours presenting with similar symptoms are malignant.14

Given the vague nature of the patient’s symptoms and the slow growth of the lesion, diagnosis was difficult. In older patients, the nature of certain presentations, coupled with the patient’s age, often results in true organic disease being overlooked. The patient in this case underwent several avenues of evaluation and persisted in her quest for a diagnosis, as she was convinced something was wrong.

This case exemplifies the need for medical and dental practitioners to work together and to share their knowledge and experience related to particular cases. Here, the orofacial examination in the facial pain clinic revealed that the associated TMD-like symptoms were more likely secondary to a neoplasm rather than primary pathology of the joint space and its surrounding structures. The situation described here is similar to a case of trigeminal neuralgia caused by an intracranial epidermoid tumour, which also occurred at Mount Sinai Hospital.15 In that case, orofacial examination in the facial pain clinic raised concern about the presence of a brain tumour, but the neurosurgeon to whom the patient was referred considered the pain to be a “dental problem.”

The experience of the patients in both of these cases underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary, even transdisciplinary, approach to the diagnosis and management of orofacial pain.15 Of course, various forms of dentoalveolar disease, including musculoligamentous conditions, can cause facial pain, and these must first be ruled out by way of a thorough history and clinical examination. Once this has been done, investigations for other conditions known to cause orofacial pain, as described here, must then be performed. It is clear that precise and open communication is necessary, not only between the patient and health care providers, but also among the health care providers themselves, and this requirement simply cannot be overstated.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Werning JW, Malyapa RS, Mendenhall NP. Salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31(1):95-9.

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editor. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyons: IARC Press; 2005.

- Laccourreye H, Laccourreye O, Cauchois R, Jouffre V, Ménard M, Brasnu D. Total conservative parotidectomy for primary benign pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: a 25-year experience with 229 patients. Laryngoscope. 1994;104(12):1487-94.

- Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: overview of a 35-year experience with 2,807 patients. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8(3):177-84.

- Gnepp DR, Henley JD, Simpson RHW, Eveson J. Salivary and lacrimal glands. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic surgical pathology of head and neck. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2009. p. 438.

- Mock D. The differential diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 1999;13(4):246-50.

- Bavitz JB, Chewning LC. Malignant disease as temporomandibular joint dysfunction: review of the literature and report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120(2):163-6.

- Grace EG, North AF. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction and orofacial pain caused by parotid gland malignancy: report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;116(3):348-50.

- Miyamoto H, Matsuura H, Wilson D, Goss A. Malignancy of the parotid gland with primary symptoms of a temporomandibular disorder. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14(2):140-6.

- Okeson, JP.American Academy of Orofacial Pain. Temporomandibular disorders. In: de Leeuw R, editor. Orofacial pain. Guidelines for assessment, diagnosis, and management. 4th ed. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co. Inc; 2008. p. 131.

- Hen MS, An BM, Lee SS, Choi SC. Use of advanced imaging modalities for the differential diagnosis of pathoses mimicking temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96(5):630-8.

- Klasser GD, Epstein JB, Utsman R, Yao M, Nguyen PH. Parotid gland squamous cell carcinoma invading the temporomandibular joint. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(8):992-9.

- Grosskopf CC, Kuperstein AS, O’Malley BW Jr, Sollecito TP.. Parapharyngeal space tumors: Another consideration for otalgia and temporomandibular disorders. Head and Neck. 2012 Feb 6. doi: 10.1002/hed.22005. [Epub ahead of print]

- Heo M, An B, Lee S, Choi S. Use of advanced imaging modalities for the differential diagnosis of pathoses mimicking temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral PatholOral Radiol Endod. 2003;96(5):630-8.

- Klieb HBE, Freeman BV. Trigeminal neuralgia caused by intracranial epidermoid tumour: report of a case. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74(1):63-5.