Intrusion of a permanent incisor

- Intrusive luxation (intrusion) is the displacement of the tooth into the alveolar bone along the axis of the tooth and is accompanied by comminution or fracture of the alveolar socket.

- According to the degree of clinical displacement, intruded teeth may be classified into 3 categories: mild intrusion (< 3 mm), moderate intrusion (3–6 mm) and severe intrusion (> 6 mm).

Presentation

Population

- Most common in children between age 6 and 12.

- More common in boys than girls.

- Intrusion of a permanent incisor is a rare injury. However, the following are the most common intrusion injury patterns.

- Intrusion without additional injury, intrusion without crown fracture, intrusion without crown–root fracture or root fracture.

- Intrusion of one or more teeth.

Signs

- Axial displacement into the alveolar bone (Fig. 1). Sometimes the tooth may not be clinically visible.

- The tooth is nonmobile.

- Percussion may give a high, metallic, ankylotic sound.

- Sensitivity test usually gives negative result.

Figure 1. Intrusion of tooth 11 (day of trauma) of an 8-year-old patient

Figure 1. Intrusion of tooth 11 (day of trauma) of an 8-year-old patient

Symptoms

Pain is not usually associated with intrusion of a permanent tooth.

Investigations

- Complete a thorough verification of medical and dental history, and record the accident in detail.

- Examine the head and facial region in order to rule out other injuries.

- Assess intraorally if there are other soft tissue and/or other dental injuries.

- Perform a radiographic investigation.

- Occlusal and periapical radiographs: on examination, the periodontal ligament space will most likely be absent from the entire root or a portion of it. The cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of the intruded tooth will appear more apical than the CEJ of the adjacent noninjured teeth (Fig. 2).

- Extraoral lateral cephalogram (or a lateral no. 4 film if a cephalogram is not available): if on clinical investigation the tooth seems to be completely intruded into the socket, rule out possible penetration into the nasal cavity.

Figure 2. Peri-apical radiograph (day of trauma): Tooth 11 is fractured and intruded severely.

Figure 2. Peri-apical radiograph (day of trauma): Tooth 11 is fractured and intruded severely.

Diagnosis

Based on clinical examination and radiographic findings, including a careful visual examination as well as a percussion test and mobility test, a diagnosis of an intruded tooth is determined.

Differential Diagnosis

Avulsion: A completely intruded tooth may give a false impression of an avulsed tooth. Radiographs should be used to rule out an avulsion injury.

Treatment

Common Initial Treatments

Managing the patient

- Alleviate the patient's psychological and functional discomfort to allow for successful treatment.

- Prescribe a systemic antibiotic treatment, and advise the patient/parents to check with the physician regarding the tetanus booster dose if external injuries are present.

- Inform the patient/parents of the diagnosis of intruded teeth and discuss potential treatment options.

- Extraoral and intraoral lacerations and wounds should be appropriately cleaned and sutured. Suturing should be delayed until reduction of the intrusion is complete, since it may hinder the positioning/splinting procedures.

- Manage other dental injuries, if required.

Managing the intruded tooth/teeth

Treatment of the intruded tooth/teeth is based on the following:

- Root development (closed vs. open apex)

- Severity of the intrusion

- Teeth with incomplete root development

- Mildly intruded (< 3 mm): Conservatively managed owing to existing eruptive potential. Allow spontaneous re-eruption and see the patient again after 2–4 weeks.

- Moderately intruded (3–6 mm): Initially, allow for spontaneous re-eruption. If no repositioning is evident within 2–3 weeks, orthodontic repositioning will be required. Referral to an orthodontist is suggested.

- Severely intruded (> 6 mm): Usually requires orthodontic repositioning if no spontaneous movement is evident in 2–3 weeks (Figs. 3 and 4). Orthodontic repositioning allows healing of the marginal bone while slowly repositioning the tooth. Surgical repositioning may be required in very severe cases, especially when there are concomitant injuries of adjacent teeth; this will also require splinting.

- Teeth with complete root development

- Mildly intruded (< 3 mm): May erupt if managed conservatively. If no movement is evident within 2–3 weeks, refer the patient to an orthodontist for orthodontic repositioning.

- Moderately intruded (3–6 mm): Requires active repositioning, using either surgical or orthodontic repositioning. In an acute phase, surgical repositioning may be done. If considerable time has passed since the injury, orthodontic repositioning is suggested.

- Severely intruded (> 6 mm): Surgical repositioning and physiological splinting for 1–2 weeks is required.

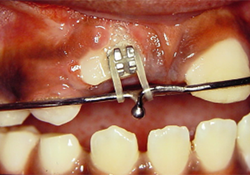

Figure 3. Surgical exposure to install orthodontic device 3 weeks following trauma.

Figure 3. Surgical exposure to install orthodontic device 3 weeks following trauma.

Figure 4. Extrusion of tooth 11 by orthodontic bonding and application of elastic force.

Figure 4. Extrusion of tooth 11 by orthodontic bonding and application of elastic force.

Where surgical repositioning is indicated, the general practitioner should decide based on clinical expertise whether to carry out the surgical repositioning or to refer the patient to a specialist.

- Referral to a specialist

- If you decide not to surgically reposition the teeth yourself, refer the patient to a pediatric dentist if the patient has immature root development or to a maxillofacial surgeon in more complex cases.

- If doing the surgical repositioning yourself

- Repositioning technique

- Administer local anesthesia.

- Gently reposition the tooth using forceps while repositioning the displaced bone by applying finger pressure both labially and lingually (palatally in most cases).

- In resistant cases, consider the possibility of bony impaction and release the impediment prior to repositioning the labial bone plate.

- Clean the affected area with saline or chlorhexidine (not recommended for open soft tissue wounds).

- Suture gingival lacerations, if any.

- Splinting of repositioned teeth

- Intruded teeth that are surgically repositioned require appropriate splinting.

- Use flexible splints (e.g., composite and wire splints) that allow physiological tooth movement to stabilize the affected tooth.

- Extend the splint to no more than 2 teeth on each side.

- Splinting method

- Ensure a dry field around the teeth to be splinted.

- Measure the length of the splint required and cut the splinting material accordingly.

- Etch the bonding surface of the teeth to be splinted with 37% phosphoric acid for approximately 20 seconds.

- Rinse thoroughly with water and gently dry with compressed air.

- Apply adhesive to the surface of the teeth to be splinted and cure as per manufacturer's instructions.

- Apply a small amount of composite on the teeth and place the splint over the composite.

- Cure the composite material according to its requirements. In cases of wire splint, some composite material has to be applied over the wire and cured again. It is easier to place the wire and the composite on the supporting teeth first and finish with the displaced tooth.

- Repositioning technique

Follow-up

- The patient should be recalled within 1 week of the accident to assess the healing process.

- Remove the splint 1–2 weeks after surgical repositioning.

- Redo a clinical and radiographic evaluation in 6–8 weeks, 6 months, 1 year and then annually for up to 5 years. Periodic assessment is essential to rule out progressive root resorption.

- Endodontic treatment should be initiated within 2–4 weeks after the trauma, when indicated.

- Teeth with complete root development: Endodontic treatment is suggested in cases of moderate to severe intrusion since there is an associated risk of root resorption in these teeth. The canal should be temporarily dressed with nonsetting calcium hydroxide paste before obturation.

- Teeth with incomplete root development: Endodontic treatment is indicated only when there are signs of pulp necrosis. Therefore, periodic assessment is essential. If endodontic treatment is required, an apical barrier should be achieved prior to obturation (by apexification/revascularization).

Advice

- Instruct the patient to follow a soft diet for 1 week and to maintain proper oral hygiene.

- Advise the patient to use a soft toothbrush and chlorhexidine rinse (0.12%) for 1 week.

- Suggest the use of a mouth guard to avoid any further injury.

THE AUTHORS

Suggested Resources

- Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, Kenny DJ, Trope M, Sigurdsson A, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fracture and Luxations of permanent teeth. Dental Traumatol. 2012;28:2-12.

- Albadri S, Zaitoun H, Kinirons MJ. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Pediatric Dentistry: Treatment of traumatically intruded permanent incisor teeth in children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20(Suppl 1):1-2.

- Al Badri S, Kinirons M, Cole B, et al. Factors affecting resorption in traumatically intruded permanent incisors in children. Dental Traumatol. 2002; 18:73-6.

- Andreasen JO, Andresen FM, Andersson L, editors. Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth, 4th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007.