Background

Across individual and cohort life spans, chronic oral conditions including dental decay and periodontal disease are mostly cumulative yet preventable. Although dental decay is also among the most frequently reported diseases worldwide, it is described as the "silent epidemic." 1 Chronic oral diseases remain unequally distributed within populations: disadvantaged groups of lower socio-economic status seem to bear most of the psychosocial and financial burden of oral diseases from childhood to the end of life.2,3 In turn, the psychosocial, economical, environmental, and biological determinants of oral health that impact various crucial moments of the life course may help to reduce or exacerbate inequities in health and oral health. Nonetheless, biomedical models and clinically focused definitions of oral health continue to prevail when causes and progression of dental decay and other oral diseases are studied.4 Given that such bio-clinical models and definitions do not account for the complex interplay of the socio-environmental, psychological, and behavioural factors of disease progression longitudinally,4 alternative theories and multilevel research approaches that foster an interdisciplinary collaboration are needed to understand the course of oral disease over time.

In turn, the life course approach emerges to explore people's lives within structural, social, and cultural contexts throughout the life span. It examines an individual's life history and the influences of life events such as marriage and divorce and biological exposures (e.g., childhood infection) on the risk of disease and other outcomes later in life.5,6 It entails a multidisciplinary paradigm to include an interplay of social and health disciplines, while directing attention to the powerful connection between individual lives and the historical and socio-economic context in which their lives unfold.7 A life course approach emphasizes a temporal and social perspective, looking back across life experiences for clues to current patterns of health and disease, whilst recognizing that both past and present experiences are shaped by the wider social, economic, and cultural contexts.

This research perspective has been successfully applied to the study oral health and disease.8,9 Nevertheless, only a few Canadian dental researchers have employed this framework to understand disease progression. There is a need to build capacity in life course perspectives to better explore the complex interplay of life events, social contexts, and biological factors in the development of oral diseases and the maintenance of oral health for life.

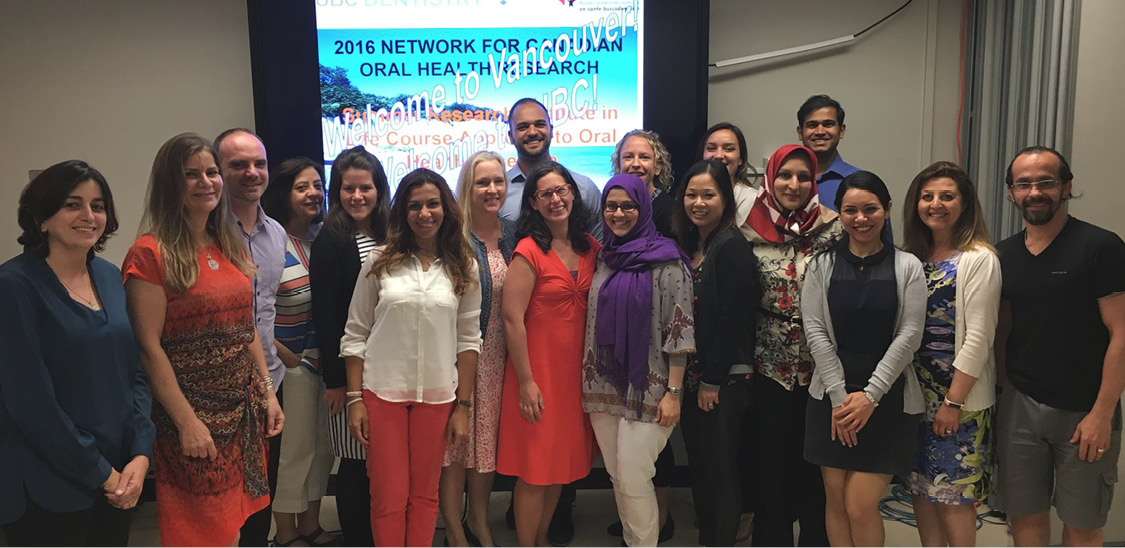

Such premises led Drs. Brondani, Amin, Nicolau, and Poon to organize and host a three-day interdisciplinary and multi-sectorial workshop in August 2016 at the University of British Columbia (UBC) Faculty of Dentistry. The workshop was funded through a grant from the Network for Canadian Oral Health Research (NCOHR) and from the UBC Faculty of Dentistry. In total, participants included 21 academics and researchers from seven Canadian dental schools with expertise in dental public health, oral health, clinical epidemiology, early childhood development, oral pathology, and pediatrics, and members from faculties of medicine and dental hygiene associations with knowledge about health services research and policy development. The workshop introduced participants to the concept of a life course approach to oral health research in both epidemiology and qualitative methodologies.

Participants evaluated the workshop as having successfully accomplished its objectives to:

- Situate the life course approach as applicable to oral health research;

- Explore the connection among live course concepts and definitions;

- Appreciate the use of qualitative and quantitative methods in life course research;

- Draft a 1-page research proposal (per each group) on the use of life course approaches in self-selected oral health topics. These research proposal drafts briefly outlined the gap in knowledge, objectives, and methods.

During the 3-day institute, a combination of presentations, group work (four groups in total), and open discussions enabled the summer institute to meet these objectives. The activities were divided into two main interdisciplinary areas: life course epidemiology and life course in social sciences. Within epidemiology, a life course approach studies the physical and social hazards during gestation, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and midlife that affect chronic disease risk and health outcomes in later life, whereas in qualitative inquiry, a life course approach focuses on the meaning of health and disease experiences across life span given time, place, the environment and the myriad of socio-political-economic circumstances.

Below are some of the summative points discussed throughout the 3 days:

- The chronic and cumulative characteristics of oral diseases and their interactions between biological, behavioural, socio-cultural, and contextual factors makes them a good fit for life course research.

- Life course as a perspective, an approach, and/or a theory is an umbrella term to both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

- Life course may be intuitive, but it is complex and requires interdisciplinary research teams to be successful.

- Longitudinal studies may not lend themselves to the life course approach. A life course theoretical conceptualization of disease causation is not only a collection of exposure data across the life course. Rather, it involves a theoretical conceptualization with a temporal ordering of exposure variables and their inter-relationships, both directly and indirectly, with the outcome of interest.

- Given the temporal ordering of events and the impact of exposure variables over time, birth cohort studies are the best fit for life course research.

- Although there is no large birth cohort in Canada yet, countries like New Zealand, United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway and Brazil, among others, offer a diversity of data from their respective studies; data acquisition may be an issue to some of these birth cohort studies.

- Those embarking in life course research should be aware of its origins, development, and application.

- A life course approach brings the bio-socio-psychological and historical-cultural pathways to oral disease development together.

The 1-page research proposal that each of the four groups developed in day 3 showed their engagement within the group while understanding the limitations of their knowledge. The research questions that the groups presented showed breadth and depth in scope, and were focused in different areas, from exploring 'the extent to which grandparents' tooth loss experiences predict the trajectory of their grandchildren's tooth loss through adulthood' to addressing 'to what extent do biological, social, and environmental factors experienced in early childhood influence the progression of early childhood caries (ECC) in children?' Now, it is up to the proponents of these research questions to answer them accordingly through research endeavours.

Future research and points for discussion:

The participants and presenters raised key points for further consideration and research, including:

- The need to differentiate between longitudinal research design and longitudinal studies using a life course approach;

- The life grid should be carefully considered as a tool to collect information throughout the life course when used in quantitative or qualitative inquiries;

- The complexity of life course research could be better entangled with the use of mixed methods research.

The workshop's complete and summary reports are available on the NCOHR website at www.ncohr-rcrsb.ca

THE AUTHORS

References

- Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005 Sep; 83(9):661–9.

- Watt G. The inverse care law today. The Lancet. 2002 Jul 20; 360(9328):252–4.

- Locker D, Maggirias J, Quiñonez C. Income, dental insurance coverage, and financial barriers to dental care among Canadian adults. J Public Health Dent. 2011; 71(4):327–34.

- Brondani M, MacEntee MI. Thirty years of portraying oral health through models: what have we accomplished in oral health-related quality of life research? Qual Life Res. 2013; 23:1087-96.

- Giele JZ, Elder GH. Methods of life course research: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage. 360 p.

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002; 31(2):285-93.

- Usita PM. Teaching about the life course perspective: a class project. Edu Gerontol. 2002; 28(2):89-98.

- Nicolau BF, Thomson MW, Steele JG, Allison PJ. Life-course epidemiology: concepts and theoretical models and its relevance to chronic oral conditions. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007; 35(4):241-49.

- Abreu LG, Elyasi M, Badri P, Paiva SM, Flores-Mir C, Amin M. Factors associated with the development of dental caries in children and adolescents in studies employing the life course approach: a systematic review. Eur J Oral Sci. 2015; 123(5):305-311.