ABSTRACT

Aims: To compare the perceptions of dentists in British Columbia regarding their decisions to provide treatment in long-term care facilities and to explore changes since 1985 in Vancouver dentists’ attitudes to treating elderly patients in such facilities.

Materials and Methods: Dentists were randomly selected from all of British Columbia in 2008 and surveyed with a similar questionnaire to that used for a 1985 study of Vancouver dentists. The attitudes of current dentists, the patterns of their perceptions and trends over time were analyzed.

Results: Of the 800 BC dentists approached for the survey in 2008, 251 replied (31% response rate). Only 37 (15%) of these respondents were providing treatment in long-term care facilities, and another 48 (19%) had stopped providing services in this setting. Among those providing care, important considerations were continuing education in geriatrics, the presence of a dental team and fee-for-service payment. The most common reasons for deciding to provide services in long-term care facilities were to increase the number of patients being served and to broaden clinical practice. Dentists who had stopped treating patients in long-term care facilities reported their perception that treating elderly people is financially unrewarding and professionally unsatisfying. The perceptions of dentists shifted substantially from 1985 to 2008. In particular, dentists responding to the 2008 survey who had never provided services in long-term care facilities were more likely to perceive administrative difficulties and a lack of financial reward as barriers than those surveyed in 1985. In addition, the proportion of Vancouver dentists with advanced education in geriatrics declined over the period between the 2 studies (75 [22%] of 334 in 1985, 10 [11%] of 87 in 2008).

Conclusion: Dentists who did not provide care for residents of long-term care facilities in 2008 seemed more likely to be deterred by administrative difficulties and financial costs than those not providing such care in 1985. In addition, fewer dentists had appropriate training in geriatrics. Continuing education, working with a dental team and payment on a fee-for-service basis were important factors for dentists who were providing care in such facilities.

Introduction

The number of senior citizens in Canada is projected to increase from 4.2 million to 9.8 million between 2005 and 2036.1 Concurrently, the rate of edentulism is decreasing, which has resulted in a high proportion of elderly patients requiring dental treatment.2-4

In the 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey―Healthy Aging, a substantial proportion (58.3%) of elderly people (≥ 65 years) living independently reported good oral health.3 However, elderly people currently residing in long-term care facilities are significantly older and frailer and are in greater need of dental care than in the past.5,6 Poor oral health adversely affects nutrition and leads to diminished social interaction.7,8

In North America, the lack of services available to elderly people living in institutions remains a concern.9,10 More specifically, lack of administrative and financial support, time constraints, difficulty in providing care and lack of training were identified as barriers to providing dental care in long-term care facilities.11-13

It has been more than 25 years since the perceptions of British Columbia dentists about the provision of care were studied. Given the aging population and the greater proportion of older people who retain their dentition, it was important to examine the attitudes and perceptions of current dentists. The aims of this survey study were to identify perceptions related to BC dentists’ decisions to treat, not to treat or to stop treating patients in long-term care facilities and to explore changes in perceptions about treating elderly patients in long-term care facilities in Vancouver since 1985.

Materials and Methods

The questionnaire created by MacEntee and colleagues11 for a 1985 survey of Vancouver dentists was used as the basis for the current study, with some additional questions to examine why current dentists had decided to treat, had stopped treating or had never treated patients in long-term care facilities. The questionnaire was pretested by a few volunteers before being administered to the study population. The final questionnaire comprised 2 sections: the first sought personal information, including sex, years in practice and postgraduate training, and the second inquired about attitudes related to providing care to frail elderly patients. All responses were based on a Likert scale (Table 1).

The British Columbia Dental Association mailed the questionnaire to 800 general dentists, selected at random according to a computer-generated random number list, who were asked to return the completed survey by fax within 1 week. At 3 and 5 weeks after the initial mailing, reminders were sent to those who had not yet responded.

SPSS version 17.0 was used for univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses. Common patterns of attitudes within each group of dentists and among groups of dentists were studied with exploratory factor analysis. This analysis is particularly useful for comparing the relative importance of a specific perception (e.g., “treating elderly patients is time-consuming”) within a complex pattern of perceptions (e.g., “decision to treat or not to treat elderly patients”). The importance of each perception within a complex pattern is defined by the magnitude of a loading value given to the specific perception. Loadings of the most important factors are close to 1.0, whereas loadings of perceptions that are of little or no importance are close to 0.0.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

Results

A total of 251 questionnaires (31%) were returned in the current study, conducted in 2008. Of the 233 respondents who provided information about urbanization, 206 (88%) were from urban areas and 27 (12%) were from rural areas. Analysis of known information about those who did not respond showed no statistically significant differences between responders and nonresponders with respect to sex, years of practice, urban vs. rural setting or location of practice.

A reliability analysis showed no statistically significant differences between answers to similarly worded questions about different aspects of care provision, which indicated an acceptable level of reliability.

For further analysis, the respondents were categorized into 3 groups: dentists who were currently treating patients in long-term care facilities (n = 37), dentists who had stopped treating patients in long-term care facilities (n = 48) and dentists who had never treated patients in long-term care facilities (n = 166).

Personal Characteristics and Attitudes of Current Dentists

The 3 groups of dentists differed significantly in terms of sex ratio (p = 0.024), location of practice (within or outside Vancouver) (p = 0.004) and preferred method of payment (p = 0.002) (Table 2). The majority of dentists who were treating elderly patients in long-term care institutions were men, and dentists providing this type of care were slightly older than dentists not treating patients in this setting. On average, dentists in all 3 groups had over 20 years of clinical experience. Dentists currently treating patients in long-term care facilities and those who had stopped treating these patients had more years of dental practice than dentists who had never treated elderly patients in long-term care facilities (p = 0.002).

A small percentage of dentists in all 3 groups had training in geriatric dentistry. Within all 3 groups, about 20% of the dentist’s patient pool consisted of patients 65 years of age or older.

In all 3 groups, a minority of respondents preferred sessional (retainer) fees as payment for services provided in long-term care facilities (Table 2). Substantially more dentists who were currently treating elderly patients in long-term care facilities (67%) than those who had never treated (48%) or who had stopped treating (48%) this patient group preferred fee-for-service payment. Proportions for fee-for-time and fee-for-service preferences were similar for dentists who had stopped providing services in long-term care facilities (48% and 48%, respectively) and for those who had never provided these services (49% and 48%, respectively).

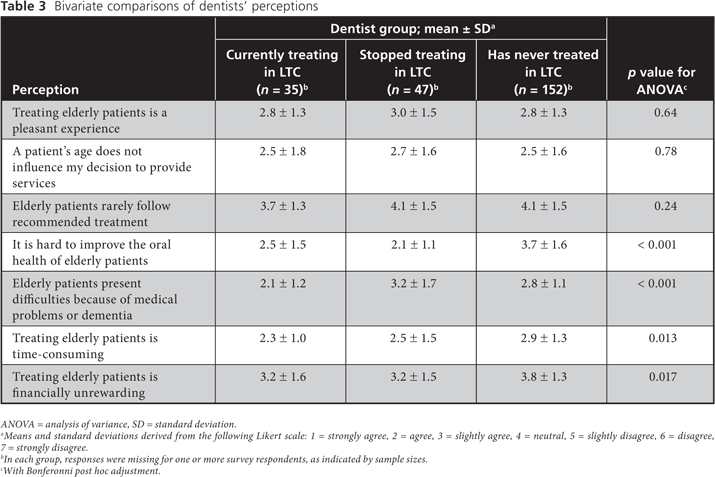

Respondents tended to agree that a patient’s age did not influence their decision to provide services, that treating elderly people in long-term care facilities was a pleasant experience, and that it is hard to improve the oral health of these patients (Table 3). They had a more neutral response to the statement that elderly patients rarely follow recommended treatment (Table 3). Dentists in all 3 groups agreed that treating elderly patients is time-consuming. Respondents who had stopped treating elderly patients in long-term care facilities were more neutral regarding the statement that these patients present difficulties because of medical problems or dementia, whereas dentists who were currently treating or had never treated these patients perceived medical problems and dementia as difficulties for service provision.

| Click on the tables to view larger versions. | ||

|

|

|

Comparisons of Perceptions about Various Aspects of Treating Elderly Patients

Attitudes and perceptions of the 3 groups of dentists in the current survey were compared by means of exploratory factor analysis, as described in the Methods section. Among dentists who were treating elderly patients in long-term care facilities, the strongest self-reported concerns were that these patients rarely follow recommended treatment (loading 0.828) and that treating elderly patients is financially unrewarding (loading 0.706) (Table 4). The latter concern was also of high importance to dentists who had stopped treating patients in long-term care facilities (loading 0.835) and to dentists who had never treated such patients (loading 0.704).

The importance of patients’ age was also perceived differently by the 3 groups of respondents. Dentists who had never treated elderly people gave more importance to patients’ age (loading 0.544) than dentists who were currently treating patients in long-term care facilities (loading 0.162) or had stopped treating these patients (loading 0.109).

The most substantial difference among the 3 groups of respondents related to perceptions that treating elderly patients was a pleasant or unpleasant experience. Dentists who were currently treating elderly patients perceived such treatment as pleasant (loading 0.516), whereas the opposite was true for dentists who had stopped treating patients in long-term care facilities (loading –0.424) and for dentists who had never treated elderly patients (loading –0.673).

Patterns of Perceptions among Dentists Currently Treating Patients in Long-Term Care Facilities

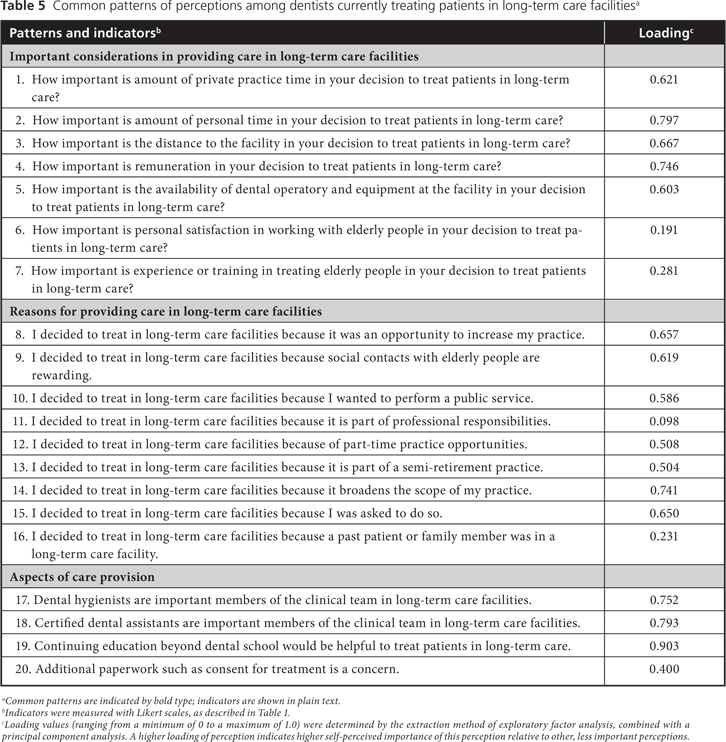

More specific insights into the perceptions of dentists currently treating patients in long-term care facilities appear in Table 5. Three common patterns of perceptions were identified: important considerations, reasons for providing care and different aspects related to the provision of care, each described in more detail below.

The 3 most important considerations in dentists’ decision to treat or not to treat elderly patients in long-term care facilities were amount of personal time (loading 0.797), remuneration (loading 0.746) and distance to the facility (loading 0.667). The least important consideration was personal satisfaction in working with elderly people (loading 0.191) (Table 5).

The most important reasons for providing care in long-term care facilities were to broaden the scope of practice (loading 0.741), to take advantage of the opportunity to increase one’s practice (loading 0.657) and being asked to work in this setting (loading 0.650). The least important reasons were that such care was part of the dentist’s professional responsibilities (0.098) and the fact that a past patient or family member was living in a long-term care facility (0.231) (Table 5).

The most important aspects of care provision were having undertaken continuing education beyond dental school (loading 0.903) and having dental hygienists (loading 0.752) and dental assistants (loading 0.793) as members of the clinical team in the long-term care facility. Having to do additional paperwork, including obtaining informed consent, was perceived as having less importance (loading 0.400) (Table 5).

| Click on the tables to view larger versions. | |

|

|

Analysis of Trends over Time: Comparison with 1985 Data

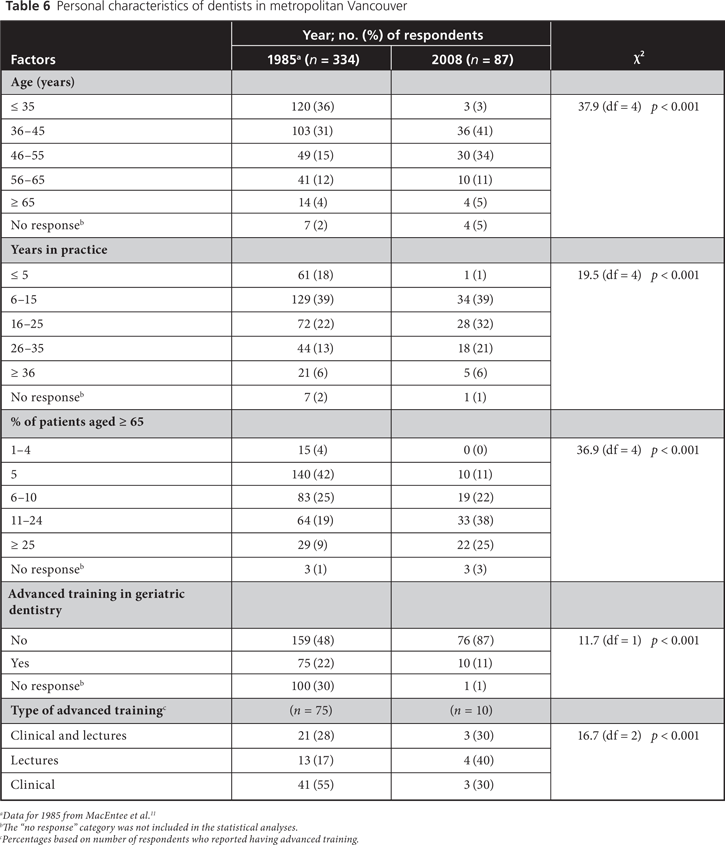

In a comparison of data obtained in a 1985 survey of Vancouver dentists and data for Vancouver respondents to the 2008 survey, respondents to the 1985 survey were younger (percentage ≤ 35 years of age 36% vs. 3%; p < 0.001) and had fewer years in practice (percentage with no more than 5 years experience 18% vs. 1%; p < 0.001) (Table 6). The 2008 cohort had a higher proportion of elderly patients (65 years of age or older) than the 1985 cohort (p < 0.001).

In both 1985 and 2008, the percentage of dentists with advanced training in geriatric dentistry was relatively low. Nonetheless, significantly more respondents to the 1985 study had this type of advanced training (22% vs. 11%) (p < 0.001).

The percentage of respondents who had never provided services to elderly people who were concerned about a lack of appropriate treatment facilities (35% vs. 29%) and the percentage who had not been asked by residents, administrators or family members to provide care in long-term facilities (56% vs. 36%) were similar in 1985 and 2008 (Table 7). Among dentists who had never provided services, a greater percentage in 2008 than in 1985 reported being too busy in private practice to undertake care of residents in long-term care facilities (38% vs. 31%; p = 0.002). Bureaucratic barriers were perceived as hindering proper treatment of patients by more of the respondents in 2008 than in 1985 (22% vs. 12%) (p < 0.001).

Among Vancouver dentists who had stopped providing services, about one-third of those responding to the 1985 survey but only 14% of those responding to the 2008 survey reported a lack of demand for services in long-term care facilities (p = 0.017). More dentists in 2008 than in 1985 identified administrative difficulties in patient management as a concern (55% vs. 12%; p < 0.001). Among respondents who stopped providing treatment in long-term care facilities, 36% of those in the 1985 survey and 55% of those in the 2008 survey reported increasing commitments to private office practice as a reason (p = 0.24). An increase in the perceived lack of financial reward was one of the main changes from 1985 to 2008 (9% vs. 48%; p < 0.001). Similarly, a greater proportion of respondents in 2008 than in 1985 perceived treating elderly patients in long-term care facilities as professionally unsatisfying (23% vs. 17%; p = 0.005).

| Click on the tables to view larger versions. | |

|

|

Discussion

This study examined perceptions of dentists who currently provide or do not provide services in long-term care facilities and compared the results with data from a similar survey conducted in 1985. In 2008, the proportions of dentists who were currently treating patients in long-term care facilities (15%) and who had stopped treating them (19%) were substantially lower than the proportion who never treated elderly patients (66%). This result confirms the previously reported concern14 that relatively few dentists decide to serve older patients. The percentage of rural dentists was higher than the percentage of urban dentists among respondents who were currently treating (19% v. 12%) and among those who had stopped treating patients in long-term care facilities (30% v. 18%). Perhaps there is more interest among rural dentists than among their urban counterparts in the issue of treating patients in long-term care facilities.

Substantial shifts in demographics and in the perceptions of dentists practising in Vancouver occurred between 1985 and 2008. Dentists responding to the 2008 survey were older, had practised longer and had more patients who were 65 years of age or older than respondents to the 1985 survey.

A lack of administrative and financial support for dental services, time constraints, difficulty in providing care and lack of training have previously been identified as barriers to providing dental care in long-term care facilities.11,13 Unfavourable working conditions in long-term care facilities were identified by 56% of dentists surveyed in Germany.15 In addition, 32% identified administrative and financial barriers as difficulties in treating patients in long-term care facilities, whereas only 5% were concerned about the patient’s age.15 In a Belgian study, 63% of respondents identified absence of dental equipment in long-term care facilities as a barrier to care.16 In British Columbia, dentists responding to surveys in 1985 and 2008 who provided dental care in long-term care facilities found the experience more pleasant than dentists who had either stopped treating or had never treated this patient population. In the present study, the required commitment of personal time and lack of remuneration were among the most important barriers identified by dentists who were currently treating patients in long-term care facilities. Another recent study showed that a majority of Canadian dentists (81%) supported a governmental role in dental care and suggested that persons in long-term care facilities should be publicly insured,17 which would alleviate some of these financial concerns.

In the present study, dentists currently serving elderly patients living in institutions reported continuing education as an important aspect facilitating their provision of care in this setting. However, among Vancouver dentists responding to the 2 surveys, only 22% of those in 1985 and 11% of those in 2008 had advanced education in geriatrics. Torrible and colleagues18 have suggested that increasing the number of undergraduate curriculum hours dedicated to geriatrics and providing positive geriatrician role models may help in addressing the poor attitudes of future medical professionals.

Data from the 1985 and 2008 surveys should be compared with caution, given that both studies had relatively low response rates, 51% and 31%, respectively. A high rate of nonresponse is a common problem in medical and dental surveys.19-24 One problem in this situation is that answers from those who do respond might differ in some systematic way from the answers that would have been provided by nonresponders. For the 2008 study, a nonresponse analysis was performed, which showed no systematic differences between responders and nonresponders in terms of sex, years of practice, urban vs. rural setting and location of practice. Given that the main focus of the present inquiry was to understand the perceptions and viewpoints of BC dentists as they pertain to providing care in long-term care facilities, nonresponse might have an additional meaning. It is possible that the proportion of all dentists not willing to provide service in long-term care facilities was even higher than that observed in the present study, since individuals who are interested in the survey topic are more likely to respond.20,25-27 In another study, reasons for nonresponse were questionnaires getting lost in other paperwork (34%), survey recipients being too busy (21%) and survey recipients choosing not to fill out the survey (16%).26 In the current study, the low response rate may reflect a lack of interest in geriatric dentistry among dental practitioners. This explanation coincides with the findings presented here, specifically that there were more rural dentists among those providing services in long-term care facilities.

The Canadian population is aging, and the majority of older people are now dentate,28 but this study indicates that only a small fraction of BC dentists are treating elderly people living in institutions. Some initiatives currently under way may help to address this situation. For example, the Canadian Dental Association has developed a position statement about access to care, which acknowledges the strengths and weaknesses of oral health care and seeks solutions to fill apparent service gaps.29 Also, if geriatric dentistry were to be accepted as a specialty program, it might become more attractive as a career path for dentists.28

Conclusion

Relatively few BC dentists responding to this survey had chosen to provide dental care in long-term care facilities, and a substantial number had decided to stop providing such services. Among those who were providing this type of service, the most important consideration was a desire to broaden their practice. Dentists treating patients in long-term care facilities usually preferred to be paid on a fee-for-service basis rather than a sessional (retainer) fee. A substantially greater proportion of respondents to this 2008 study than to a similar study conducted in 1985 identified administrative difficulties in patient management as a barrier to providing this type of care.

THE AUTHORS

References

- A portrait of seniors in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2006. Catalogue No. 89-519-XIE.

- Ramage-Morin PL, Shields M, Martel L. Health-promoting factors and good health among Canadians in mid- to late life. Health Rep. 2010;21(3):45-53.

- Oral health: edentulous people in Canada 2007 to 2009. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada. 2010. Catalogue No. 82-625-X.

- Alian AY, McNally, ME, Fure S, Birkhed D. Assessment of caries risk in elderly patients using the cariogram model. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(5):459-63.

- McNally L, Gosney MA, Field EA, Doherty U. The dental status of elderly in-patients. Age Ageing. 1998;27(Suppl 1):P47-8.

- Robichaud L, Durand PJ, Bédard R, Ouellet JP. Quality of life indicators in long-term care: options of elderly residents and their families. Can J Occup Ther. 2006;73(4):245-51.

- Pino A, Moser M, Nathe C. Status of oral healthcare in long-term care facilities. Int J Dent Hyg. 2003;1(3):169-173.

- MacEntee MI. Missing links in oral health care for frail elderly people. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(5):421-5.

- Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigon JM. editors. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

- Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: report of the Institute of Medicine on racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(4):S1377-81.

- MacEntee MI, Weiss RT, Waxler-Morrison NE, Morrison BJ. Opinions of dentists on the treatment of elderly patients in long-term care facilities. J Public Health Dent. 1992;52(4):239-44.

- Weiss RT, Morrison BJ, MacEntee MI, Waxler-Morrison NE. The influence of social, economic, and professional considerations on services offered by dentists to long-term care residents. J Public Health Dent. 1993;53(2):70-5.

- Weeks JC, Fiske J. Oral care of people with disability: a qualitative exploration of the views of nursing staff. Gerodontology. 1994;11(1):13-7.

- Bryant SR. MacEntee MI, Browne A. Ethical issues encountered by dentists in the care of institutionalized elders. Spec Care Dentist. 1995;15(2):79-82.

- Nitschke I, Ilgner A, Müller F. Barriers to provision of dental care in long-term care facilities: the confrontation with ageing and death. Gerodontology. 2005;22(3):123-9.

- De Visschere LM, Vanobbergen JN. Oral health care for frail elderly people: actual state and opinions of dentists towards a well-organized community approach. Gerodontology. 2006;23(3):170-6.

- Quiñonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Canadian dentists’ opinions on publicly financed dental care. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69(2):64-73.

- Torrible SJ, Diachun LL, Rolfson DB, Dumbrell AC, Hogan DB. Improving recruitment into geriatric medicine in Canada: findings and recommendations from the geriatric recruitment issues study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(9):1453-62.

- Charlton R. Research: is an ‘ideal’ questionnaire possible? Int J Clin Pract. 2000; 54(6):356-9.

- Hovland EJ, Romberg E, Moreland EF. Nonresponse bias to mail survey questionnaires within a professional population. J Dent Educ. 1980; 44(5):270-4.

- Bonetti D, Johnston M, Clarkson J, Turner S. Applying multiple models to predict clinicians’ behavioural intention and objective behaviour when managing children’s teeth. Psychol Health. 2009; 24(7): 843-60.

- Hirschman KB, Corcoran AM, Straton JB, Kapo JM. Advance care planning and hospice enrollment: who really makes the decision to enroll? J Palliat Med. 2010;13(5):519-23.

- Gillespie SM, Gleason LJ, Karuza J, Shah MN. Health care providers’ opinions on communication between nursing homes and emergency departments. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(3):204-10. Epub 2010 Jan 18.

- Gordan VV, Bader JD, Garvan CW, Richman JS, Qvist V, Fellows JL, et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for occlusal primary caries among dentists in the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(2):171-84.

- Locker D. Response and nonresponse bias in oral health surveys. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60(2):72-81.

- Kaner EF, Haighton CA, McAvoy BR. ‘So much post, so busy with practice--so, no time!’: a telephone survey of general practitioners’ reasons for not participating in postal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract. 1998; 48(428):1067-9.

- Groves RM, Presser S, Dipko S. The role of topic interest in survey participation decisions. Public Opin. Q. 2004;68(1):2-31.

- Ettinger RL. The development of geriatric dental education programs in Canada: an update. J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a1.

- Canadian Dental Association. CDA position on access to oral health care for Canadians. May 2010. Available: www.cda-adc.ca/_files/position_statements/CDA_Position_on_Access_to_Oral_Health_Care_for_Canadians.pdf