A 67-year-old man with a history of oral lesions for at least 1 year presented for evaluation. He complained of “white” lesions, primarily on his buccal mucosa, that were symptomatic; i.e., he experienced burning sensations at rest and during mastication. He denied taking any new medications, eating new foods or using new oral hygiene products at the time of symptom onset.

His past medical history was significant for hypertension, mixed hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes and spinal stenosis. His past surgical history was unremarkable. Current medications included ASA, esomeprazole, irbesartan, metformin, pravastatin and tadalafil. He reported no known drug or food allergies, and family/social history was non-contributory.

A review of systems was unremarkable, and clinical examination revealed a well-nourished, well-developed man in no apparent distress. Facial and extraoral skin was unremarkable. Intraoral examination revealed diffuse areas of Wickham striae with erythema on the buccal mucosa and generalized erythema of the posterior maxillary gingiva bilaterally. Clinical diagnosis was consistent with oral lichen planus (OLP) and an incisional biopsy of the left buccal mucosa demonstrated histopathology consistent with OLP. The patient was prescribed topical corticosteroid and prophylactic antifungal rinses and his condition improved significantly.

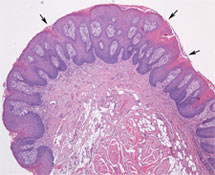

The patient presented regularly for routine evaluation, and 1 year after his initial diagnosis, he developed a 0.5-cm asymptomatic papillary lesion on the right lateral surface of the tongue within an OLP focal area (Fig. 1). An excisional biopsy of the lesion was completed and histopathologic analysis revealed hyperkeratotic, papillary, acanthotic squamous epithelium containing a diffuse proliferation of foamy histiocytes subjacent to the basement epithelial cells and between rete pegs (Figs. 2, 3).

Figure 1: A 0.5-cm papillary lesion on the right lateral surface of the tongue surrounded by Wickham striae associated with oral lichen planus.

Figure 1: A 0.5-cm papillary lesion on the right lateral surface of the tongue surrounded by Wickham striae associated with oral lichen planus.

Figure 2: Papillary, acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with surface clefts that contain orange-pink-stained parakeratin (arrows). The rete pegs are uniformly elongated. (Hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 4×).

Figure 2: Papillary, acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with surface clefts that contain orange-pink-stained parakeratin (arrows). The rete pegs are uniformly elongated. (Hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 4×).

Figure 3: Foamy macrophages found between the rete pegs and primarily within the connective tissue papillae. (Hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 20×).

Figure 3: Foamy macrophages found between the rete pegs and primarily within the connective tissue papillae. (Hematoxylin and eosin, magnification 20×).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the tongue lesion consisted of traumatic fibroma, verruciform xanthoma and several lesions associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), including squamous papilloma, focal epithelial hyperplasia, verruca vulgaris, condyloma acuminatum and verrucous carcinoma.

What is the diagnosis?

Discussion

Traumatic fibroma

Traumatic fibroma is a common benign soft tissue lesion resulting from a continuous repair process that includes production of mature collagen in a fibrous submucosal mass.1 This lesion most commonly develops from direct trauma to the mucosal surfaces, often as a result of a parafunctional habit or a poorly fitting dental prosthesis.2 Clinically, these lesions often appear as dome-like growths with a smooth surface the colour of normal mucosa.2 The most common sites for development of traumatic fibromas are the tongue, labial and buccal mucosa.1

Routine histopathology reveals epithelium overlying a mass of dense, fibrous connective tissue composed of collagen, fibroblasts and chronic inflammatory cells.2 The overlying surface epithelium may exhibit hyperkeratosis, with or without foci of ulceration secondary to chronic trauma.2

The recommended treatment for this lesion is surgical excision; recurrence is uncommon, but may result from repetitive trauma at the same site.1

Oral HPV-associated lesions

HPVs are small DNA viruses that have been associated with widespread disease, ranging from benign warts to invasive carcinoma, that affects mucosal and cutaneous surfaces.3 Clinically, oral HPV-associated lesions may present in a variety of ways and are largely benign.1,3,4 Transmission of HPV has not been clearly explained, but may occur through direct mucosal contact, fomite transfer and autoinoculation.3 HPV subtype differentiation is not possible with routine histopathologic staining; rather, in situ hybridization, immunohistochemical analysis and polymerase chain reaction techniques are required.3 If surgical removal is recommended as treatment of any oral HPV-associated lesion, the lesion should be excised with a blade rather than a laser to avoid creating a plume containing viral particles, which may inoculate adjacent cells.1

Squamous papilloma (SP) — SP is the most common papillary lesion of the oral mucosa. It may occur on any intraoral site, but is most commonly observed on the ventral tongue, frenal area, palate and lip mucosal surfaces.1,4 This lesion is often associated with HPV types 6 and 11.4,5 SP most commonly appears as an exophytic, pedunculated solitary lesion that is pink to white in colour.4 Multiple SP lesions can be seen in those with immunosuppressive conditions, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, and have been associated with HPV type 16, which has a greater association with malignant transformation.6 Histopathologically, SP lesions have multiple finger-like projections of stratified squamous epithelium containing central vascularized connective tissue.1,4 HPV-altered cells in the upper-level epithelium may demonstrate pyknotic nuclei (condensation into a solid, dark mass) and crenated nuclei surrounded by an edematous or optically clear zone, i.e., koilocytes.4 The treatment of choice is surgical excision, and the recurrence rate is low in immunocompetent people.1,4

Focal epithelial hyperplasia (FEH) — FEH (Heck disease) most commonly affects the labial/buccal mucosa and tongue and is associated with HPV types 1, 6, 13 and 32.3,5 Clinically, these lesions often present as multiple, soft, flat or convex papules that are slightly paler than the surrounding mucosa and are asymptomatic.5 The most prominent histologic feature of FEH is acanthosis, with wide rete ridges that may be confluent or club-shaped.5 In addition, koilocytes are consistently observed in the superficial layers of the epithelium of these lesions.3 The lesions often resolve spontaneously, but may be prolonged; therefore, excision may be clinically indicated.5 This diagnosis was unlikely in the case presented, but should be included in a discussion of oral HPV-associated lesions.

Verruca vulgaris (VV) — VV (common skin wart) most commonly presents intraorally on the palate or keratinized gingival tissue.1 VV has been associated with several HPV types, including types 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 11, 16, 40 and 57.1,3,5 Clinically, VV appears as firm, sessile exophytic lesions with a white appearance.3 Histopathologic analysis of VV reveals epithelial projections with pronounced hyperparakeratotic tips accompanied by hyperorthokeratosis on the sides of the upward projections.1 Dilatation of capillaries often occurs, and a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate may be present in the supporting connective tissue.5 The treatment of choice for VV is surgical excision.

Condyloma acuminatum (CA) — CA, which is extremely rare in the oral cavity, is characteristically observed in the anogenital region.1,3 Oral CA lesions are most commonly described as multiple, small pink-white nodules that often converge to form soft sessile lesions. They are often seen on the gingival mucosa, lips and labial commissures, when present.1,3 CA can be associated with several HPV types, including 2, 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33 and 35, and it is more commonly seen in patients with HIV.1,5 The histopathology of CA is similar to SP, but HPV-related viral changes are always seen (i.e., koilocytes are present in the superficial layers of the epithelium).1,5 Surgical excision is the recommended treatment for CA lesions.

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) — A form of squamous cell carcinoma with specific clinical and histopathologic features, VC has been associated with HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18.3,7 VC is strongly associated with chronic use of tobacco, snuff and betel quid and is most commonly seen on intraoral surfaces that come into contact with these materials (i.e., the buccal mucosa, mandibular alveolar crest, gingiva and tongue).7,8 It often appears as an asymptomatic thick white plaque resembling cauliflower. These lesions tend to be slow growing, exophytic, well circumscribed and are often locally aggressive.3,7 Regional lymph nodes may be enlarged and symptomatic secondary to inflammation induced by VC.7 Histopathology of VC often reveals a heavily keratinized, irregular surface with parakeratin clefting and plugging. Bulbous hyperplasia is evident in the prickle-cell layer, but the basement membrane is well defined and intact.3,7 Surgery is considered the primary treatment for VC and may be used in combination with radiotherapy, especially in patients with extensive lesions.7

Verruciform xanthoma (VX)

In the case described above, the clinical and histopathologic findings are most consistent with VX.

VX is a rare, benign lesion commonly presenting as a solitary papillomatous mass.9 It affects the oral cavity predominantly, with extraoral cases reported primarily in the genital area.9 Most often found on the gingiva and alveolar ridges,10,11 VX lesions are characterized as slow growing and solitary, with a granular surface whose colour can range from that of normal mucosa to red, depending on the degree of keratinization.12,13 Histopathologic features of VX include hyperplasia and parakeratosis of the squamous epithelium, acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges and numerous xanthomatous (“foamy”) cells in the connective tissue papillae.13 Treatment of VX consists of surgical excision; the prognosis is excellent, and the recurrence rate is extremely low.11,14

It has been suggested that VX may represent an immune-associated response to localized epithelial trauma resulting in the release of membranous lipid components into the adjacent connective tissue, phagocytosis of lipids by tissue macrophages and the accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages in connective tissue papillae.11 VX has been reported concomitantly with OLP, without a specific causal relationship between the two conditions10,14,15; however, VX and OLP may stimulate a similar underlying immunological response.16 Recently, VX has been reported as a clinical finding in a case series of patients who developed graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem-cell transplant.9

The biopsy was curative for our patient, and no recurrence of the VX lesion has been observed. The patient’s OLP continues to be managed effectively with topical corticosteroid and prophylactic antifungal rinses.

Despite its characteristic appearance, VX may be mistaken clinically for benign or more aggressive types of oral lesions. It is imperative for oral health care providers to have a thorough understanding of oral soft tissue lesions to provide optimal patient care.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Esmeili T, Lozada-Nur F, Epstein J. Common benign oral soft tissue masses. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(1):223-40, x.

- Stoopler ET, Alawi F. Clinicopathologic challenge: a solitary submucosal mass of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(4):329-31.

- Kumaraswamy KL, Vidhya M. Human papilloma virus and oral infections: an update. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7(2):120-7.

- Jaju PP, Suvarna PV, Desai RS. Squamous papilloma: case report and review of literature. Int J Oral Sci. 2010;2(4):222-5.

- Feller L, Khammissa RA, Wood NH, Marnewick JC, Meyerov R, Lemmer J. HPV-associated oral warts. SADJ. 2011;66(2):82-5.

- Stoopler ET, Balasubramaniam R. Images in clinical medicine. Human papillomavirus lesions of the oral cavity. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):e37.

- Alkan A, Bulut E, Gunhan O, Ozden B. Oral verrucous carcinoma: a study of 12 cases. Eur J Dent. 2010;4(2):202-7.

- Santoro A, Pannone G, Contaldo M, Sanguedolce F, Esposito V, Serpico R, et al. A troubling diagnosis of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma (“the bad kind” of keratosis) and the need of clinical and pathological correlations: a review of the literature with a case report. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:370605. Epub 2010 Oct 25.

- Shahrabi Farahani S, Treister NS, Khan Z, Woo SB. Oral verruciform xanthoma associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease: a report of five cases and a review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5(2):193-8. Epub 2011 Feb 9.

- Polonowita AD, Firth NA, Rich AM. Verruciform xanthoma and concomitant lichen planus of the oral mucosa. A report of three cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28(1):62-6.

- Yu CH, Tsai TC, Wang JT, Liu BY, Wang YP, Sun A, et al. Oral verruciform xanthoma: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(2):141-7.

- Platkajs MA, Scofield HH. Verruciform xanthoma of the oral mucosa. Report of seven cases and review of the literature. J Can Dent Assoc. 1981;47(5):309-12.

- Visintini E, Rizzardi C, Chiandussi S, Biasotto M, Melato M, Di Lenarda R. Verruciform xanthoma of the oral mucosa. Report of a case. Minerva Stomatol. 2006;55(11-12):639-45.

- Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Takata T, Ogawa I. Verruciform xanthoma — biological profile of 282 oral lesions based on a literature survey with nine new cases from Japan. Oral Oncol. 2003;39(4):325-36.

- Miyamoto Y, Nagayama M, Hayashi Y. Verruciform xanthoma occurring within oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25(4):188-91.

- Oliveira PT, Jaeger RG, Cabral LA, Carvalho YR, Costa AL, Jaeger MM. Verruciform xanthoma of the oral mucosa. Report of four cases and a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2001; 37(3):326-31.