Abstract

Pink porcelain was used in a custom zirconia abutment with a zirconia implant-supported anterior crown to compensate for a malposed anterior implant with horizontal bone deficiency and lack of keratinized tissue. This clinical procedure was able to reduce abutment height, mask the horizontal defect and create a symmetrical and esthetic effect.

Implant placement in the esthetic zone requires comprehensive diagnosis and treatment planning to achieve optimal results. Key factors include the quality of bone, the quantity of bone in both vertical and horizontal dimensions and soft tissue architecture.1 Careful consideration of these will yield a predictable and successful outcome for both the patient and clinician.2

Implant placement, especially in the anterior maxilla, should be prosthodontically driven.1 Diagnostic wax-ups are required to determine ideal tooth position for placement, emergence profile, esthetics and occlusion. The dental surgeon must consider whether clinical conditions support implant placement. Favourable conditions include thick tissue and intact bone walls, whereas unfavourable ones include thin tissue and a facial bone defect.3 Implant treatment should satisfy both the functional and esthetic needs of the patient.3

When faced with a case in which implant placement has been imperfect and facial bone support has been compromised, the clinician is obliged to remedy the situation.4 Although implant repositioning and augmentation would be ideal, consideration of the patient may necessitate a compromised solution. In this article, we describe the use of pink porcelain to manage a compromised implant supported anterior crown.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old male with a noncontributory medical history presented with a failed post and core anchoring a porcelain crown on tooth 22 (Fig. 1). Clinical and radiographic examination revealed a fractured crown with mild localized periodontitis. The tooth was deemed unrestorable. Treatment options included an implant-supported crown, a fixed 3-unit bridge from tooth 21 to tooth 23, a removable cast or transitional partial denture or no treatment. The patient decided to proceed with an implant-supported crown.

Clinical Procedures

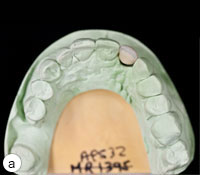

Immediate implant placement at the time of extraction of tooth 22 was planned. However, following extraction, a fenestration in the buccal plate was observed. The implant procedure was aborted. Bio-Oss (Geistlich, Wolhusen, Switzerland) was used for ridge augmentation and the site was closed to allow for 3 months of healing. Impressions were taken to aid in treatment planning and the fabrication of a temporary partial removable prosthesis (Fig. 2).

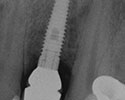

During implant surgery 3 months later, a flap was raised and osteotomy performed. A 13-mm-long, 3.5-mm-wide NobelActive narrow platform implant (Nobel Biocare, Richmond Hill, ON) was placed according to standard surgical protocols. A healing cap was placed and a postoperative radiograph was taken to confirm the implant’s position. The edentulous area was stabilized with a removable transitional acrylic partial denture. Postoperative examination at 1 week showed healing within normal limits.

After 5 months, the patient returned for assessment. Radiographic and clinical examination suggested that osseous integration and healing were within normal limits (Fig. 3). The implant body was positioned facially and horizontal bone deficiency and minimal attached gingiva were observed (Fig. 4). Lingually, the gingiva had migrated over the healing cap, and an Odyssey Diode laser (Ivoclar Vivadent, Mississauga, ON) was used to expose the cap for removal. Working casts were created and a provisional screw-retained temporary abutment and acrylic crown were fabricated. Gingival recontouring was given a 4-week healing period (Fig. 5).

When the patient returned for final impressions, the provisional prosthesis was removed and an impression coping was placed. Periapical radiography confirmed seating (Fig. 6). A closed-tray polyvinyl siloxane impression was taken using Take1 Advanced light body (Kerr, Orange, CA) and Aquasil Ultra Heavy (Dentsply, Woodbridge, ON). A matching shade was selected, and the provisional prosthesis was replaced. Occlusion was adjusted and verified.

NOTE: Click to enlarge images.

Laboratory Component

The impression was poured with stone, modeled with the PINDEX system (COLTENE, Cuyahoga Falls, OH) and assessed for preparation of the final prosthesis. The laboratory prescription requested a custom Procera (Nobel Biocare) abutment with a cervical collar in pink porcelain. The objective was to reduce the height of the abutment, mask the horizontal defect and create a symmetric, esthetic effect.

A NobelProcera zirconia custom abutment (Nobel Biocare) with cervical Creation ZI pink porcelain (Jensen Dental, North Haven, CT) (Fig. 7) and a Lava zirconia (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN) full ceramic crown (Fig. 8) were returned by Rotsaert Dental Laboratory Services Inc. (Hamilton, ON). The Lava zirconia crown was layered with feldspathic Lava Ceram porcelain (3M ESPE). The abutment and crown were placed on the master cast to assess for fit, occlusion and esthetics (Fig. 9).

When the patient returned for placement of the prosthesis, the provisional appliance was removed and the abutment seated (Fig. 10). A periapical radiograph confirmed seating (Fig. 11). The crown was positioned and assessed for internal fit, marginal integrity, occlusion and esthetics. The abutment was then torqued to specification (35 Ncm). The abutment screw was protected with polyvinyl siloxane and the crown was cemented with Fujicem (GC America, Alsip, IL) (Fig. 12). Occlusion was adjusted and verified (Fig. 13), and the patient was given postoperative instructions. He returned for a 48-hour post-cementation assessment, which was unremarkable (Fig. 14).

Figures 9a, b and c: Occlusal, lingual and frontal views of the final restoration on the master cast.

Temporizing with Pink Composite

In this case, pink porcelain was used in the laboratory. Pink composite can also be employed in a clinical setting to achieve optimal esthetic results. Micerium (Avegno, Italy) supplies light-cured composite in several shades. Although pink composite was not used in this case, the material was applied to the patient’s provisional prosthesis to demonstrate the effect (Fig. 15). The material is simple to use and effective in terms of results.

Figures 15 a and b: Pink composite material applied to the provisional prosthesis to demonstrate the effect.

Discussion

The placement of an anterior implant in the esthetic zone requires careful diagnosis and treatment planning. When faced with a significant horizontal bone deficiency, an autogenous graft remains the ideal option.5 However, patient factors, cost and time may affect treatment choice, and an alternative may be required.

In our case, the facial positioning of the implant predisposed the situation to facial bone resorption.6 Subsequently, the lack of bone facially resulted in the lack of attached gingiva,6 presenting both an esthetic and functional issue. A connective tissue graft was recommended in the near future to try to optimize gingival health.5

The use of pink composite during the provisional phase improves esthetics during healing. The clinical use of light-cured pink composite is a simple yet effective approach, which also aids in the selection of pink porcelain for the laboratory component.

The use of pink porcelain through laboratory requisition is a simple option that optimizes esthetics and masks compromised surgical outcomes. Pink porcelain materials not only blend with soft tissue, but also maintain esthetics over time.

Conclusions

The availability of pink materials has increased significantly and provides the restorative clinician with a new armamentarium for improving esthetics when presented with a difficult and compromised surgical result.

Surgical placement of an implant in a less than ideal position creates a dilemma for the clinician. Although surgical intervention may be warranted, the patient may not approve the treatment and request an alternative solution. Pink materials — used as composite with a provisional prosthesis and as porcelain with an abutment and final restoration — have the ability to mask a defect and create a symmetric and esthetic result, offering resolution for both the patient and clinician.

THE AUTHORS

References

- Martin WC, Morton D, Buser D. Pre-operative analysis and prosthetic treatment planning in esthetic implant dentistry. In: Buser D, Belser U, Wismeijer D, editors. ITI Treatment Guide. Volume 1: Implant Therapy in the Esthetic Zone: Single-Tooth Replacements. Berlin: Quintessence; 2007. p. 11-9.

- Buser D, Martin WC, Belser UC. Surgical considerations for single-tooth replacements in the esthetic zone: standard procedure in sites without bone deficiencies. In: Buser D, Belser U, Wismeijer D, editors. ITI Treatment Guide. Volume 1: Implant Therapy in the Esthetic Zone: Single-Tooth Replacements. Berlin: Quintessence; 2007. p. 26-31.

- Chen S, Buser S. Factors influencing the treatment outcomes of implants in post-extraction sites. In: Buser D, Wismeijer D, Belser U, editors. ITI Treatment Guide. Volume 3: Implant Placement in Post-Extraction Sites: Treatment Options. Berlin: Quintessence; 2008. p. 18-42.

- Sammartino G, Marenzi G, di Lauro AE, Paolantoni G. Aesthetics in oral implantology: biological, clinical, surgical, and prosthetic aspects. Implant Dent. 2007;16(1):54-65.

- Chen S, Buser S. Implants in post-extraction sites - a literature update. In: Buser D, Wismeijer D, Belser U, editors. ITI Treatment Guide. Volume 3: Implant Placement in Post-Extraction Sites: Treatment Options. Berlin: Quintessence; 2008. p. 9-15.

- Degidi M, Nardi D, Daprile G, Piattelli A. Buccal bone plate in the immediately placed and restored maxillary single implant: a 7-year retrospective study using computed tomography. Implant Dent. 2012;21(1): 62-6.

| Gallery of all Figures in article. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|