Abstract

A patient presented with long-standing symptoms of neuropathic pain in the upper jaw. There were no signs of infection, and the patient had been told by several dentists and physicians that there was no evidence of any pathology. Investigations eventually revealed the source of the problem as failure of root canal treatment. Diagnosis of neuropathic pain (and other orofacial neurogenic disorders) is often a process of exclusion, and this case underscores the need for clinicians to eliminate all possible causes before reaching that conclusion.

Dentists see people in pain every day. Fortunately, in most cases the cause of the pain is relatively easy to diagnose, with periodontal disease, pulpitis (reversible or irreversible), infection and myalgia being the most common causes.1 Cracked tooth syndrome, vertical root fractures, myofascial pain and temporomandibular joint disorders may present with greater complexity, but can, with patience, be accurately diagnosed.2-4 However, atypical odontalgia, trigeminal neuralgia and neuropathic pain often present difficult diagnostic challenges.5 Accurately determining the source of a patient’s pain and selecting the most appropriate management technique should always be the goal.

Case Report

A 30-year-old woman presented with pain in the upper right jaw. She reported that she had been experiencing constant, throbbing pain for over 5 years. She noted that it began after she underwent root canal therapy on tooth 16 and that since then, she had never been completely pain-free.

In the years between the initial treatment and the current presentation, she had seen 2 general dentists, both of whom reported no sign of infection or failure of root canal therapy, and 2 endodontists, who similarly advised that no endodontic treatment was necessary. She had also had a consultation with an ear, nose and throat surgeon, who confirmed no identifiable pathology. In Russia, her country of origin, she saw another physician, who took a brain scan to eliminate any pathology of the central nervous system. The patient did not know whether the mode of imaging had been computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging,6 but she reported that it too had yielded negative results.

The patient reported that she had recently completed 3 courses of an antibiotic (amoxicillin), which had provided no relief. In response to questioning, she reported that she had tried nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen, ketorolac), acetaminophen and acetaminophen with codeine, but nothing relieved the pain. She was frustrated and desperate for help.

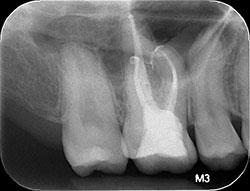

The patient’s medical history was noncontributory. Radiographic examination showed acceptable root canal therapy of tooth 16, but no treated fourth canal on the mesiobuccal (MB) root could be visualized (Fig. 1). There was no sign of apical pathology on any teeth in the first quadrant. Palpation of the soft tissues showed profound mechanical allodynia: all of the buccal tissues were extremely tender to the lightest touch; all of the teeth from the canine to the second molar were equally sensitive to percussion; and teeth 13, 14, 15 and 17 were equally sensitive to cold, although none produced a lingering ache. All probing depths were within normal limits (as far as could be discerned, given that all tissues were exquisitely tender to any touch), and no swelling or sinus tract was visible.

The tooth had been restored with a direct composite, but no cracks on the clinical crown could be seen on microscopic examination.

Discussion of the potential diagnosis and required treatment included the possibility of neuropathic pain, such as atypical odontalgia. The patient asked that the tooth be extracted, as she could not take the pain any longer. It was explained that extraction might not resolve the pain and could actually worsen it. It was also explained that there was no overt reason to perform root canal retreatment; however, the clinician suggested that retreatment be started, with the idea of looking for vertical cracks after the old root filling material had been removed. The clinician was not optimistic about the chance of success with retreatment, but the diagnosis of neuropathic pain could be reached only by excluding all other potential pathologies, including failure of the previous root canal therapy.

Tooth 16 was anesthetized with articaine 4% with 1:200,000 epinephrine and lidocaine 2% with 1:100,000 epinephrine as a buccal infiltration. The tooth was isolated with a rubber dam, and the existing composite restoration was removed to ensure full exposure of the visual field and access to the pulp chamber. Three treated canals were observed, but the root fill (gutta-percha) had a “dirty” or “sludgy” appearance, consistent with infection. After removal of the gutta-percha, all canals were cleaned and shaped using a combination of hand and rotary files. An untreated mesiobuccal 2 (MB2) canal was located and was also negotiated to length. All canals were irrigated with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite, and the smear layer was removed after instrumentation with 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The canals were then dried, and final microscopic inspection under high magnification revealed no cracks whatsoever. Calcium hydroxide was injected to length in all canals, and restoration was accomplished with a cotton pellet and temporary endodontic restorative material. Although no purulent or serous drainage was observed, there was a distinct odour that is typically present when teeth with failing root canal therapy are instrumented.

The patient was given clindamycin 300 mg 1 tablet t.i.d. for 7 days and dexamethasone 2 mg 1 tablet t.i.d. for 3 days. As is typical with clindamycin therapy, the patient was advised to take a probiotic (e.g., yogurt and Lactobacillus acidophilus) in conjunction with the antibiotic, and to discontinue the drug therapy immediately if any significant adverse effects developed, such as diarrhea or a rash.

At the scheduled follow-up appointment, 4 weeks later, the patient reported that she had experienced immediate relief from her pain. Before administration of anesthetic, the patient’s teeth and tissues were examined, but no tenderness to palpation or percussion was found in the first quadrant . The root canal retreatment was completed without complication (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Preoperative radiograph showing adequate root fill and no apical pathology.

Figure 1: Preoperative radiograph showing adequate root fill and no apical pathology.

Figure 2: Postoperative radiograph showing the final root fill.

Figure 2: Postoperative radiograph showing the final root fill.

Discussion

Diagnosis of neuropathic pain is a process of exclusion. It involves methodically ruling out localized pathology in the form of odontogenic infection, periodontal disease, cracked teeth, caries or failed root canal therapy. This case underscores the responsibility of the attending clinician to be as thorough as possible when evaluating a patient who is experiencing pain. The patient may present with a variety of symptoms, rather than classical signs, and a comprehensive approach may be required to parse out the underlying etiology.7 In the case presented here, all of the dentists and physicians who examined the patient, including the current author, were certain that there was a neurogenic basis for her pain; nonetheless, it seemed worthwhile to investigate whether the tooth was cracked or the root canal therapy was failing. Retreatment was undertaken primarily because of the patient’s insistence and was ultimately successful. After years of frustration, this patient became her own greatest advocate. This case emphasizes the importance of the initial interview with any patient.

THE AUTHOR

References

- Kim JK, Baker LA, Seirawan H, Crimmins EM. Prevalence of oral health problems in U.S. adults, NHANES 1999-2004: exploring differences by age, education, and race/ethnicity. Spec Care Dentist. 2012;32(6):234-41.

- Manolopoulos L, Vlastarakos PV, Georgiou L, Giotakis I, Loizos A, Nikolopoulos TP. Myofascial pain syndromes in the maxillofacial area: a common but underdiagnosed cause of head and neck pain. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(11):975-84.

- Mathew S, Thangavel B, Mathew CA, Kailasam S, Kumaravadivel K, Das A. Diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012;4(Suppl 2):S242-4.

- Gonçalves DA, Camparis CM, Franco AL, Fernandes G, Speciali JG, Bigal ME. How to investigate and treat: migraine in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(4):359-64.

- Clark GT. Persistent orodental pain, atypical odontalgia, and phantom tooth pain: when are they neuropathic disorders? J Calif Dent Assoc. 2006;34(8):599-609.

- Ibrahim S. Trigeminal neuralgia: diagnostic criteria, clinical aspects and treatment outcomes. A retrospective study. Gerodontology. Gerodontology. 2012 Oct 3. doi: 10.1111/ger.12011. [Epub ahead of print]

- Oshima K, Ishii T, Ogura Y, Aoyama Y, Katsuumi I. Clinical investigation of patients who develop neuropathic tooth pain after endodontic procedures. J Endod. 2009;35(7):958-61.